Reflection

Designing with animals as the user introduces

several difficulties compared to traditional

human-computer interaction.

Communication is the most obvious barrier: unlike

humans, animals cannot directly express needs or provide feedback.

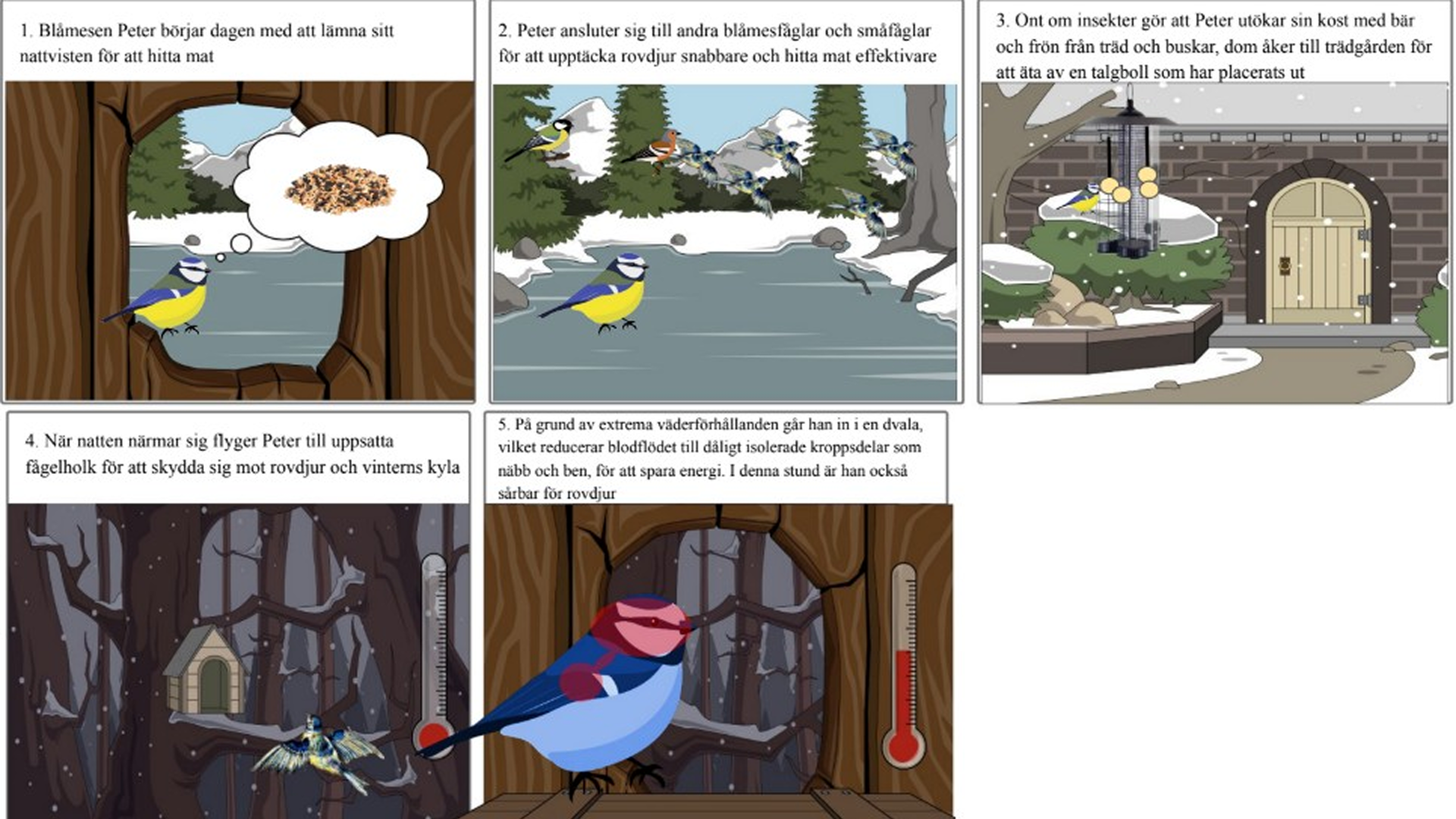

Because of this, methods such as interviews had

to be discarded in our project, and we instead relied on

desk research, observations, and

insights from bird experts. A key risk here is

that our assumptions about animal behaviour may

be biased by human interpretation, which can reduce the

reliability of the design process.

Another challenge is that the user group cannot be involved in

iterative evaluation in the same way as humans.

Testing with real animals often requires a very

high level of fidelity, which can be

costly, time-consuming, and

ethically complex. There is also a risk of

unintended ecological consequences, since

supporting one species may negatively impact another.

From the course, we learned the importance of adapting

human-centred design methods to animal contexts.

Observations and personas proved

valuable, but we had to rethink their purpose: not as direct

feedback tools, but as ways to empathise with animals through

expert knowledge and

biological insights. Ultimately, the course

taught us to be more reflective,

critical, and creative in

approaching non-human interaction.

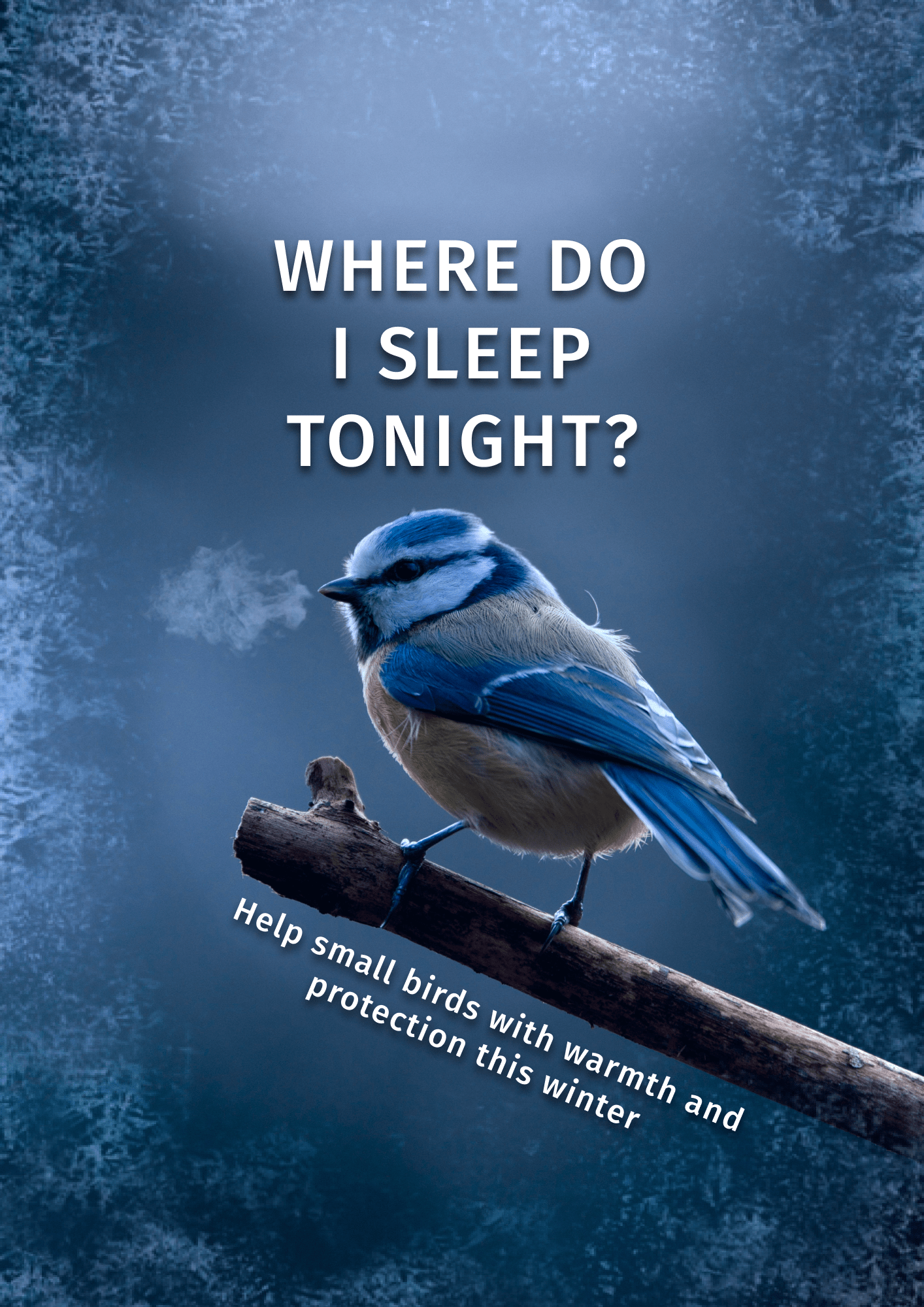

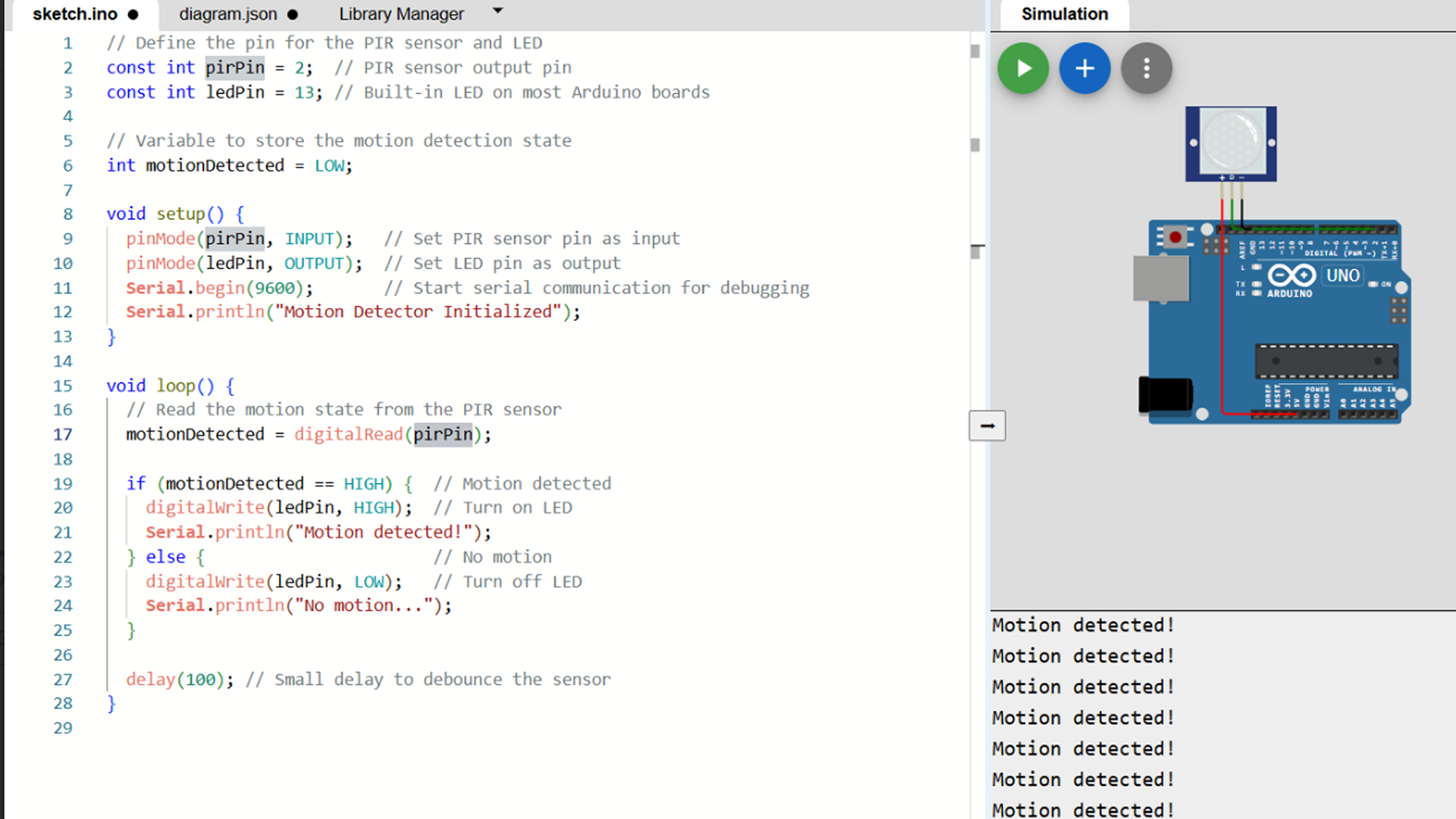

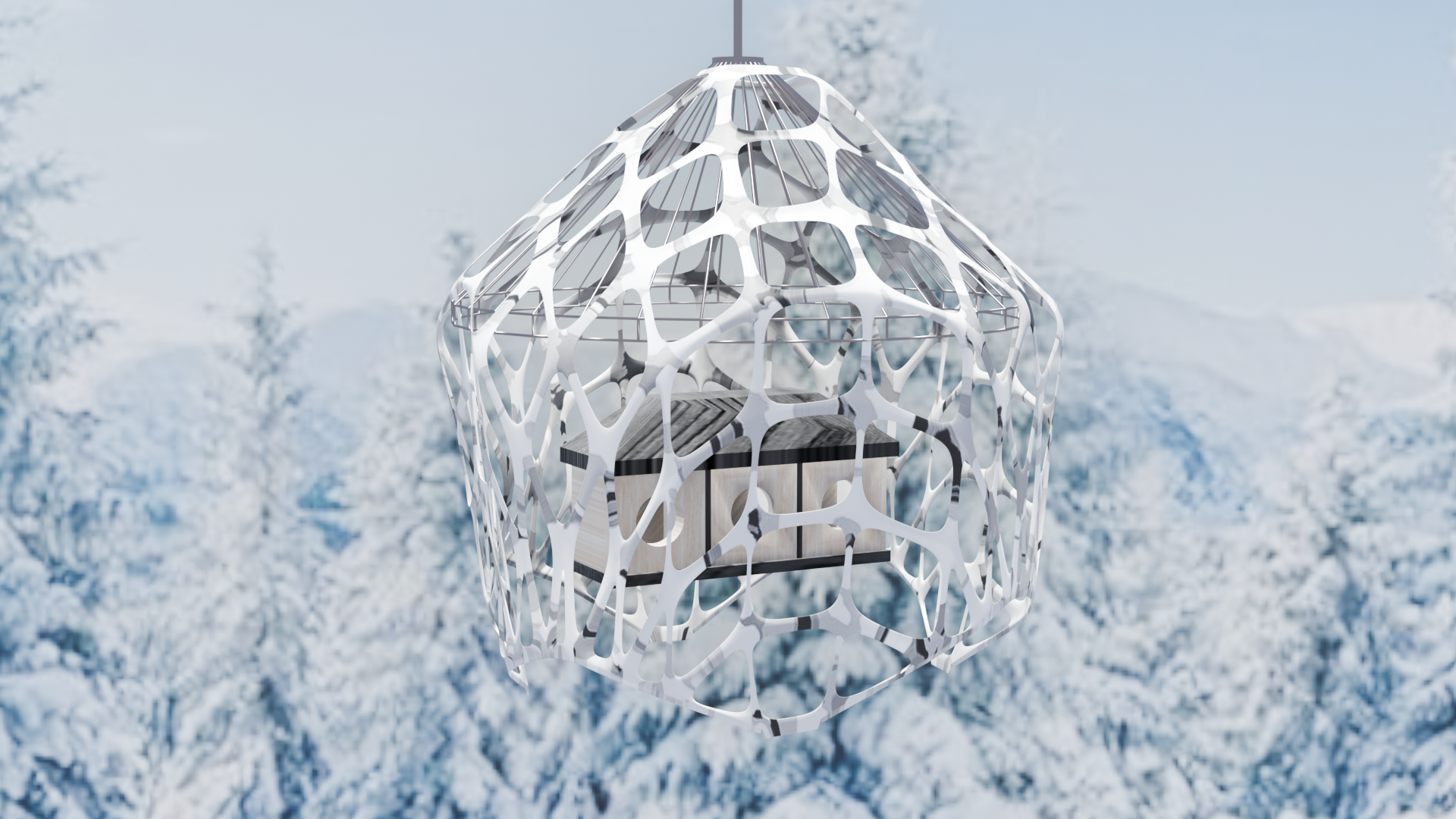

At the end of the course, all participants showcased their

final products in an exhibition. Each team

presented not only the prototype, but also a

selling poster, a

design thinking poster, and a

brochure documenting the process and illustrating

key steps with photos. This final presentation

tied the project together and highlighted the value of

communicating both process and outcome.